How to use a skill/will matrix to adjust your management style

Library → Models and frameworks → Skill/will matrix

The four stages of learning any process.

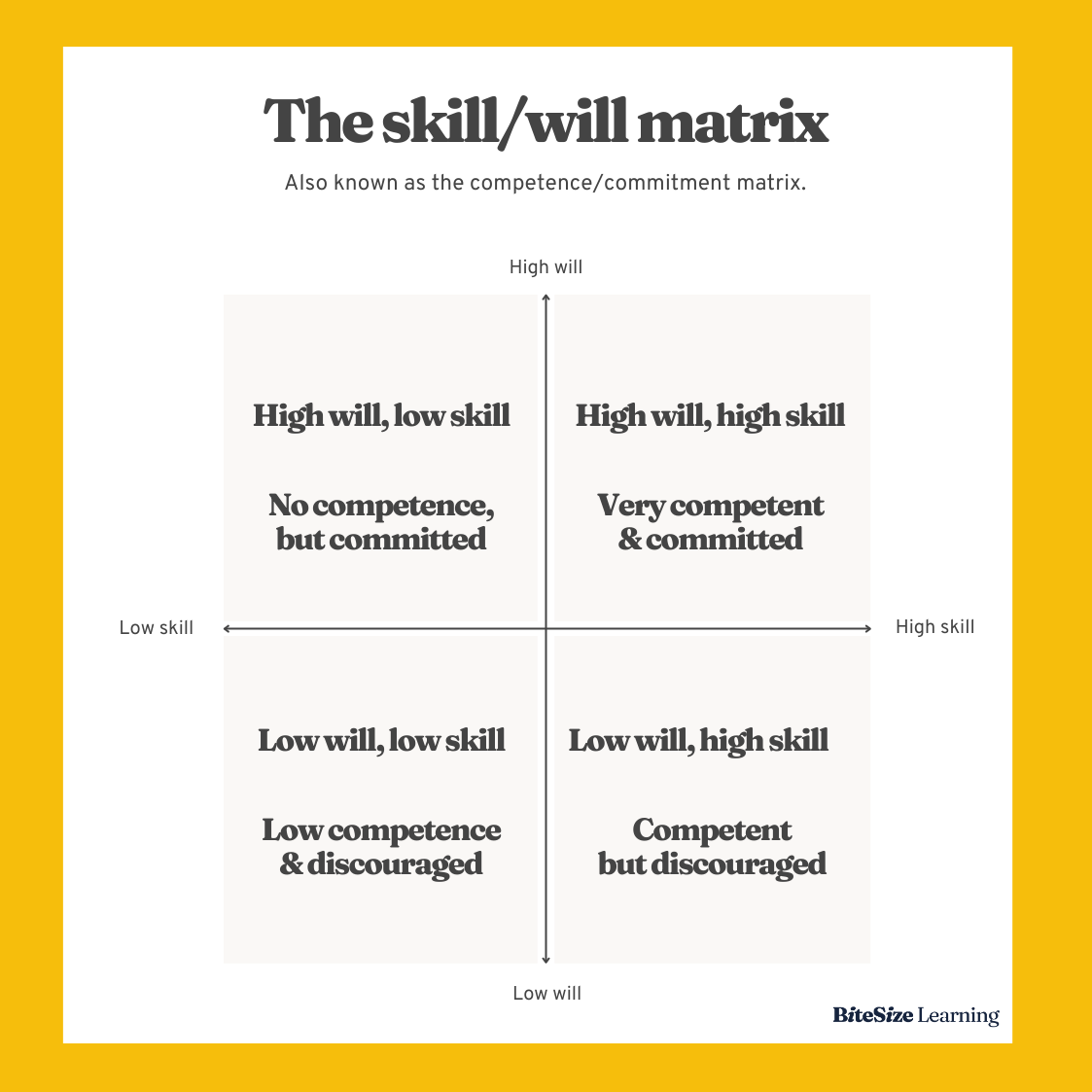

The Skill/Will matrix – also known as the Competence/Commitment matrix – is a powerful management tool. The related concept of ‘situational leadership’, or ‘leadership style’

People in a role can have varying levels of skill (competence) and will (commitment)

When people take on new responsibilities, their skill usually grows over time, but their motivation and confidence can ebb in the middle of the process, as they struggle to master their new role

Different kinds of management support are called for, depending where an employee is on their journey

By mapping their reports onto this matrix, managers can respond in the most helpful way: whether by providing close instruction, boosting motivation, or providing extra autonomy. This is sometimes called ‘leadership style’ or ‘situational leadership’

The four quadrants of the skill vs. will matrix

Let’s take a look at the basic skill/will matrix.

A simplistic interpretation (more on that soon) is that a person can be in one of four skill/will quadrants:

Low Skill, High Will: Individuals in the top-left corner are highly motivated but lack the necessary skills or experience. They are eager to learn and contribute, but they need guidance and training to develop their abilities.

Low Skill, Low Will: Individuals in the bottom-left quadrant lack both skills and motivation. They may be new to the role or organization, or they may be disengaged for some other reason. These people need the most help.

High Skill, Low Will: In the bottom-right quadrant, individuals have have high competence, but lack the motivation to put their skills to use. They know how to do the job, but for one reason or another, they're not committed. This could be due to a variety of factors, such as lack of confidence or dissatisfaction with the job. These individuals often need support in finding their motivation, or addressing obstacles that are blocking their commitment.

High Skill, Low Will: The heady top-right corner is the quadrant of self-reliance. Individuals in this quadrant are experienced, skilled, and motivated. They have a clear understanding of what needs to be done and the drive to do it. They are often the 'stars' of the team, requiring little supervision and providing significant contributions.

As you reflect on these four professional situations, you might feel like you’ve spent time in each of the four boxes at some point in your career. And that’s no surprise – when it comes to learning new skills, starting a new job

A learning journey through the skill/will matrix

From a brave beginner to a motivated master, learning a new skill often sends people on a journey through all four boxes.

The creative process has famously been described as: ‘This is awesome. This is tricky. This sucks. I suck. This might be OK? This is awesome.’ In the same way, embarking on any new project or challenge often requires a journey through the dark valley of doubt before we can make it to the sunlit uplands of the other side. Let’s break it down:

The high-will, low-skill beginner

We get that longed-after promotion, and we start our new role full of enthusiasm and readiness to learn.

We’re probably trained up on some of the simpler responsibilities at the start, and hey – they don’t seem too bad! Maybe we’re going to be a real natural at this? We’re in our ‘This is awesome!’ era. Little do we know, there is so much more to come…

The low-will, not-very-skilled novice

Soon enough, we start to enter a dark period of overwhelm.

We are rapidly discovering an intimidating list of ‘things we need to learn’ – and the list is getting longer faster than we can learn the things on it. Although we’re managing to do complete some of our duties, we are failing miserably at others, and somehow, genuine excellence feels further away than when we started? Our self-confidence reaches its lowest ebb, and not without reason – we’re now painfully aware just how bad we are!

The low-will, but increasingly-skilled apprentice

As time goes by, we steadily improve – but our confidence is yet to match our competence.

The problem is, our hard-won improvement has taken a lot longer than our joyful beginner thought it would, so however good we are, we still feel ‘behind schedule.’ Ugh.

A faint whisper of imposter syndrome still troubles the senses. Although our aptitude is growing daily, like a frog in a gently warming pot, it’s happened too gradually to really notice. Yes, we’re starting to accept that ‘This might be OK?’ But when it comes to major challenges, we’re still shying away from stepping up and putting our new-found knowledge to the test.

The high-will, high-skill master

Finally, we hit our stride.

As our experience grows and provides evidence that we’ve got what it takes, our confidence increases to match our abilities. We can cheerfully learn from our occasional setbacks, without faith in ourselves being shaken too deeply. When things go well, we sometimes surprise ourselves at just how good we can be. From time to time, other people even turn to us for advice. Feels pretty good! We’re back at ‘This is awesome!’ Time to apply for another promotion?

This is a long-winded way of demonstrating that spells of anxiety and discouragement in any role are part-and-parcel of the learning process. Although there are plenty of ways to be pointlessly miserable at work, this is the kind of stress that might suggest you’re quietly growing, improving, and pushing out of your comfort zone. So if you find yourself thinking ‘This sucks! I suck!’, consider you might just be on a glorious journey from Box 1 to Box 4, via Boxes 2 and 3.

Situational leadership: using different leadership styles based on skill & will

Directive management for high-will, low-skill beginners

These individuals are often eager to learn and contribute, but they lack the necessary skills or knowledge. This situation calls for a straight-forward directive leadership style. Here's how you can manage them:

Direct instruction: Provide clear, step-by-step instructions and demonstrate how tasks should be done. They need a clear path to follow.

Training and development: Invest in their skills development. This could be through formal training, online courses, or on-the-job training

Patience and encouragement: Remember, they're just starting to develop their skills. Be patient, encourage their enthusiasm, and appreciate their efforts.

Close coaching for low-will, low-skill strugglers

Although it seems like people in this quadrant have ‘both problems’, they’re actually closely connected – they’ll become more motivated as they improve! It’s not a lost cause.

Move towards a coaching style: as they start to improve, pull back slightly on direct instruction and support them in figuring things out for themselves. Ask thoughtful questions to get them thinking, and give a subtle push in the right direction rather than simply solving problems for them. Some self-directed ‘wins’ tactfully engineered via your coaching skills will help them build much-needed confidence.

Goal setting: Set small, achievable goals to help them see progress and build confidence. Try to take their focus off the ‘Big List’ of everything they need to master, and onto the immediate tasks ahead. It’s ‘one foot in front of the other’ time.

Positive reinforcement: Celebrate their achievements, no matter how small. This can help to boost their morale and motivation.

Develop one dimension at a time: in some roles it might be appropriate for an employee to learn things ‘perfectly’ and then gradually get faster – a la ‘Slow is smooth, and smooth is fast.’ In others, it might be better to insist on an ambitious cadence of work to rapidly build experience and reduce wariness of the task, while tolerating a few missteps along the way. Try not to insist on multiple types of progress at once – deliberate practice is all about improving on very specific aspects of a process, one at a time.

Supportive management for low-will, more-skilled lurkers

These individuals are now quite competent, but ae lack the confidence to perform at their best.

Supportive leadership: These people are quite possibly better than they realise – make it clear you believe in their abilities, and their capacity to surprise themselves.

Raise the cadence: they may have performed Task X a few times before, but it’s still something of a deliberate, anxious process that they’d rather avoid. Cheerfully assume that they didn’t just ‘get lucky’ but are perfectly able to do it again and again! Consider sharply raising the tempo, so they rack up a lot of experience at their new-found talent.

Check for psychological safety: people in this quadrant might be able to do X on a good day, but worry about messing up. Is there anything about the team, your management, their social style or your workplace culture that is causing this? As well as spelling out lofty goals and drop-dead must-dos, show some vulnerability and make it clear there’s space for imperfection on the journey.

Consider other motivation-killers: sometimes high-skill high-will people slip back into this quadrant because their motivation has slipped for some other reason. In that case, you may need to take a different approach.

Feedback and recognition: regularly provide constructive feedback and acknowledge their efforts and improvements

Mentorship: Pair them with a mentor who can provide guidance, share experiences, and boost their confidence.

Delegating to high-will, high-skill stars

These individuals have reached a high level of skill and motivation. They can often work independently and are invaluable assets to any team. Here, a laissez-faire approach might do the job,

Autonomy: give them the freedom to manage their own work. Trust them to make decisions and solve problems on their own.

Challenging projects: keep them engaged by providing new challenges and delegating 'senior-level’ work that will stretch their skills and keep them learning.

Recognition and rewards: ensure their contributions are recognized and rewarded. Show them that their work is valued and appreciated.

Remember, effective management is about adapting your style to meet the needs of each individual. Understanding where each team member sits on the Skill/Will matrix can help you provide the right kind of support and guidance, leading to a more motivated and productive team.

Some final observations on the skill/will matrix

The Skill/Will matrix is a potent tool for managers, but it also has its subtleties and complexities. Understanding these nuances can help you use the matrix more effectively. Here are some key points to consider:

Skill and will are not fixed: they vary by task

It's important to remember that an individual's placement on the matrix is not static, but can vary depending on the task or skill at hand. For instance, a team member might be highly skilled and motivated when it comes to project management but less competent and enthusiastic about data analysis. Likewise, if you suddenly delegate a lot of new duties to someone because they’re ‘super-motivated’, you might be surprised to find their motivation suddenly craters.

So, a manager needs to evaluate their team members' skills and motivation in the context of specific tasks or roles. You might benefit from providing close instruction on one aspect of their role, gently coaching on another, and freely delegating in a third area.

Factors that influence skill & will outside of the learning & development journey

Diverse motivational drivers: People are driven by a range of different factors. Some may be motivated by the intrinsic satisfaction of doing a job well, while others may be more focused on extrinsic rewards such as pay or recognition. Understanding what motivates each team member can help managers boost their will and engagement. A one-size-fits-all approach to motivating others is likely to be less effective than a tailored approach that takes into account individual drivers.

The influence of external factors: The matrix focuses on skill and will, but there are many other factors that can impact an individual's performance, including personal circumstances, physical and mental health, and workplace culture. Managers need to be aware of these external influences and consider them when assessing team members and planning interventions.

The Dynamic Nature of the Matrix: People's skills and motivation can change over time due to factors like training, experience, personal development, or changes in their personal life. Regular check-ins and conversations can help managers stay updated on these changes and adjust their management style accordingly.

Balancing individual and team needs: While the Skill/Will matrix is a tool for managing individuals, managers also need to consider the dynamics of the team as a whole. For example, focusing too much on high-performing individuals can demotivate those who are struggling. Conversely, spending too much time on less competent or committed team members can lead to resentment from those who are more self-reliant.

The Skill/Will matrix is a tool, not a formula. It provides a valuable framework for understanding and managing people, but it needs to be applied thoughtfully and flexibly, taking into account the complexities of human behavior and the diverse factors that influence performance.